The Beverly Hills of Chicago: The South Side’s Quiet Ridge of Stability

Jan 06, 2026

Introduction

Beverly is a residential neighborhood on Chicago’s Far South Side, bounded by 87th Street to the north, 107th Street to the south, Western Avenue to the west, and Vincennes Avenue to the east. Built along a natural ridge that rises above the surrounding prairie, Beverly has long been shaped by its topography, rail access, and suburban development patterns. Unlike many South Side neighborhoods defined by industry, Beverly developed primarily as a commuter-oriented residential community, a distinction that continues to define it today.

Trivia Question:

Which Beverly street is known for containing one of the largest continuous collections of historic residential architecture in Chicago?

Beverly by the Numbers

The Landscape Before Development

Long before Chicago expanded southward, the land that would become Beverly was part of a glacial ridge formed thousands of years ago. This ridge runs diagonally across the South Side, cutting against the city’s otherwise uniform grid. Elevated above the surrounding prairie and wetlands, the ridge offered natural drainage and a vantage point that distinguished it from nearby low-lying areas.

Prior to European settlement, the area was inhabited and traveled by Native American tribes, including the Potawatomi. The ridge served as a natural route for movement and trade across the region. While few physical traces of this period remain, the geography that shaped early Indigenous use of the land later influenced how settlers and developers viewed its potential.

Early European Settlement

European settlement in the Beverly area began in the mid-19th century, largely driven by Irish immigrant families. Many of these early settlers were drawn to the area after working on major infrastructure projects, including the Illinois and Michigan Canal and the expanding railroad network. Seeking farmland and permanent homes, they established small agricultural operations along the ridge.

Irish Catholic families became the dominant early population, giving the area a distinct cultural and religious identity that persisted well into the 20th century. Churches, parish schools, and extended family networks played a central role in community life. This early settlement pattern laid the foundation for Beverly’s later reputation as a stable, family-oriented neighborhood.

Railroads and the Birth of a Commuter Community

The defining factor in Beverly’s transformation from farmland to neighborhood was the arrival of the railroad. The Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad established tracks through the area in the 1850s, but it was not until the late 19th century that regular commuter service made residential development viable.

Rail stations along the line allowed residents to travel downtown while living at a distance from the city’s industrial core. This connection positioned Beverly as one of Chicago’s earliest true commuter suburbs, even before it was formally annexed into the city.

Housing development followed the rail line closely, with homes clustered near stations and gradually extending outward along the ridge. Unlike factory-adjacent neighborhoods, Beverly’s growth was not tied to a single employer or industrial corridor, which helped insulate it from the economic volatility that affected other parts of the South Side.

Annexation and Municipal Integration

Beverly was annexed by the City of Chicago in 1890, earlier than many surrounding communities. Annexation brought access to city services such as water, sanitation, and public schools, while allowing the neighborhood to retain its low-density residential character.

Despite annexation, Beverly continued to function socially and physically like a suburb. Large lots, detached homes, and winding streets distinguished it from denser areas closer to the city center. The elevated ridge limited large-scale commercial or industrial development, reinforcing the neighborhood’s residential focus.

Early 20th Century Growth

The early decades of the 20th century marked a period of steady growth for Beverly. Improved rail service, rising incomes, and demand for single-family homes fueled new construction. Architectural styles reflected national trends of the period, including Victorian, Prairie School, Arts and Crafts, and various revival styles.

Longwood Drive emerged as one of the neighborhood’s most prominent residential corridors. Lined with architecturally significant homes, it became a symbol of Beverly’s affluence and stability. Today, the street remains one of the largest continuous collections of historic residential architecture in Chicago.

Churches and schools expanded alongside housing. Catholic parishes in particular played a central role, reinforcing Beverly’s Irish Catholic roots. Public schools and private academies helped anchor families to the neighborhood across generations.

The Great Depression and World War II

The Great Depression slowed development but did not fundamentally destabilize Beverly. High rates of homeownership and the absence of heavy industry helped buffer the neighborhood from mass unemployment and abandonment. While some families faced hardship, the area avoided the severe disinvestment seen elsewhere.

World War II brought renewed economic activity and population growth. Returning veterans and postwar families contributed to a housing boom that extended into the 1950s. New homes were built alongside older structures, maintaining the neighborhood’s predominantly single-family character.

Postwar Era and Demographic Change

For much of the early and mid-20th century, Beverly remained overwhelmingly white and Irish Catholic. Like many neighborhoods across the United States, it faced questions of integration during the postwar period. However, demographic change in Beverly occurred more gradually than in other parts of Chicago.

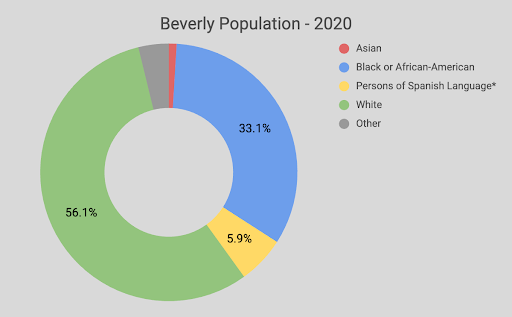

Beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, Black middle-class families began moving into the neighborhood. Unlike areas that experienced rapid white flight, Beverly became known for its comparatively stable racial integration. Community organizations, churches, and local leadership played a role in easing transitions and maintaining neighborhood cohesion.

By the late 20th century, Beverly had developed a reputation as one of Chicago’s most racially integrated neighborhoods, with a strong emphasis on homeownership and civic engagement.

Preservation and Historic Identity

As Chicago evolved, Beverly’s residents increasingly focused on preservation. The neighborhood’s architectural diversity and distinctive street patterns became points of pride. Several historic districts were designated to protect key areas, including portions of Longwood Drive and the Ridge.

Preservation efforts helped limit large-scale redevelopment and maintained the neighborhood’s residential scale. While this approach constrained new construction, it reinforced Beverly’s long-standing identity and appeal to families seeking stability.

Commercial Activity and Daily Life

Beverly has never been a major commercial hub. Retail and services are concentrated in small clusters near rail stations and along major streets. Local businesses tend to serve neighborhood needs rather than attract regional traffic.

This limited commercial footprint has contributed to the area’s quiet character but has also posed challenges related to economic growth and retail diversity. Residents often travel outside the neighborhood for employment and specialized services.

Transportation and Connectivity

Transportation continues to shape life in Beverly. The neighborhood is served by multiple stations on the Metra Rock Island District line, providing direct access to downtown Chicago. This rail service remains one of Beverly’s defining features, supporting its commuter-oriented lifestyle.

Major arterial roads, including Western Avenue and 95th Street, connect the neighborhood to surrounding areas, while the elevated ridge continues to influence street design and traffic patterns.

Beverly in the 21st Century

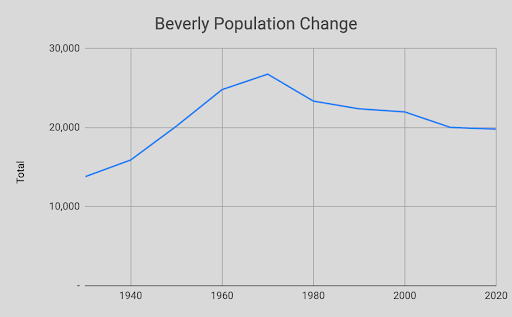

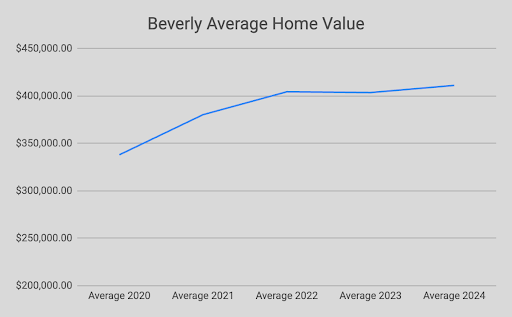

Today, Beverly remains a largely residential neighborhood characterized by single-family homes, mature trees, and long-term residents. Challenges include aging infrastructure, rising maintenance costs for historic homes, and broader population shifts affecting Chicago as a whole.

At the same time, Beverly benefits from strong neighborhood organizations, active schools, and continued demand for housing. Its reputation for stability and integration remains intact, even as the city around it continues to change.

Beverly is Unique

Beverly represents a different model of South Side development, one shaped by geography, rail access, and suburban planning rather than industry. Its history complicates simplified narratives about urban decline and highlights the role of early infrastructure decisions in shaping long-term outcomes.

As Chicago continues to grapple with uneven investment and population change, Beverly stands as an example of how planning, preservation, and community continuity can influence a neighborhood across generations.

Trivia Answer

Longwood Drive. The Longwood Drive Historic District extends twelve blocks from 9800 to 11000 S. Longwood Dr. and from 10400 to 10700 S. Seeley Ave. Unique in the city for its hilly topography; Longwood Drive is dominated by a natural ridgeline. The houses in this district include several different architectural styles, such as Italianate, Prairie School, Queen Anne, and Renaissance Revival, and are the works of noted turn of the century architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.