New City: The History of Stockyards Strength on Chicago’s South Side

Sep 10, 2025

New City, Community Area 61, is a neighborhood forever linked to the history of Chicago’s meatpacking industry and the iconic Union Stock Yards. Located on the South Side, it’s bounded by Pershing Road to the north, Garfield Boulevard to the south, Racine Avenue to the east, and Western Avenue to the west. Today, New City is often divided into two distinct communities: Back of the Yards, historically tied to the stockyards, and Canaryville, a tight-knit Irish enclave. Together, they tell a story of immigration, labor battles, resilience, and reinvention.

Trivia Question:

What famous 1906 novel, inspired by the brutal conditions of the Union Stock Yards in New City, sparked national outrage and led to sweeping food safety reforms in the United States?

(Answer at the end of this post.)

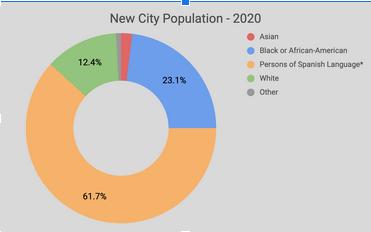

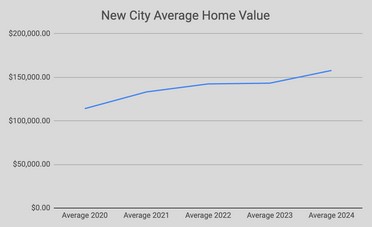

New City by the Numbers

Origins and Early History

New City’s history is inseparable from the Union Stock Yards, which opened in 1865 and quickly became the meatpacking capital of the world. The stockyards drew tens of thousands of immigrants—Irish, German, Polish, Lithuanian, Slovak, and later Mexican workers—who settled in the neighborhood’s modest homes and worked grueling hours in the plants.

The stockyards not only provided jobs but also defined life in the area. The air was thick with the smell of livestock and industry, and the neighborhood pulsed with the rhythms of whistles, factory shifts, and union meetings. Canaryville, meanwhile, grew as an Irish stronghold, known for its working-class toughness and fierce neighborhood loyalty.

Transformation and Evolution

By the early 20th century, New City was one of Chicago’s most densely populated working-class neighborhoods. Churches, corner taverns, and social halls served as anchors for immigrant life, while labor struggles—including the 1886 Haymarket movement and the 1894 Pullman Strike—were deeply tied to stockyard workers.

After World War II, Mexican immigrants began to settle in Back of the Yards, joining the European families already present. Over time, the Latino community grew, and by the late 20th century, it became the area’s cultural backbone. When the Union Stock Yards closed in 1971, the neighborhood lost its economic center, forcing residents to adapt through grassroots organizing and community development efforts.

The Union Stock Yards: Innovation, Labor, and Black Contributions

The Union Stock Yards were more than just a collection of slaughterhouses and rail spurs—they were the beating heart of America’s meat industry for over a century. From their opening in 1865 until their closure in 1971, the stockyards made Chicago the meatpacking capital of the world, processing billions of animals and feeding an industrializing nation.

The yards transformed how America thought about food, transportation, and labor. Innovations such as the disassembly line (a forerunner to Henry Ford’s assembly line) and refrigerated rail cars revolutionized efficiency and distribution. These breakthroughs allowed Chicago to dominate the meatpacking trade, sending pork, beef, and lamb to every corner of the country. By the turn of the 20th century, it’s estimated that nearly 80% of U.S. meat passed through Chicago’s Union Stock Yards, underscoring its unmatched role in the nation’s economy.

Black Workers in the Stock Yards

African Americans played a pivotal, though often overlooked, role in this industrial machine. During the Great Migration (1916–1940), tens of thousands of Black Southerners came to Chicago in search of steady work and a chance to escape Jim Crow laws. The stockyards became one of their main employers. While Black workers were often relegated to the toughest, dirtiest, and most dangerous jobs—such as killing floors, hide cellars, or rendering plants—they became essential to the industry’s functioning.

This influx of Black labor shifted Chicago’s demographics and laid the foundation for communities like Bronzeville to flourish. It also sparked interracial labor tensions, culminating in moments such as the Chicago Race Riot of 1919, where competition for jobs between white ethnic workers and new Black arrivals was one of the key flashpoints.

Inventions and Contributions

Few people know that the industrial advances perfected in the stockyards—like industrial refrigeration, cold storage warehouses, and by-product industries (soap, glue, leather, fertilizer)—relied heavily on the relentless labor of Black workers. Though the patents and credit usually went to white industrialists, Black workers’ muscle and knowledge sustained the system.

One notable contribution tied to Black history was the role of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen of North America, which eventually began to integrate under pressure from Black workers demanding fairer treatment. By the mid-20th century, Black union activism in the yards not only reshaped labor rights in Chicago but also contributed to the broader Civil Rights Movement, as labor justice became intertwined with racial justice.

Key Part of American History

The Union Stock Yards weren’t just a Chicago story, they were an American story. They fueled the nation’s westward expansion, shaped global food distribution, and created a blueprint for modern industrial production. And while their legacy includes harsh exploitation, it also tells of resilience and progress, especially the ways Black workers carved out a place for themselves in an industry that tried to exclude them, laying the groundwork for greater labor and civil rights in the decades to come.

Historical Landmarks and Structures

Union Stock Yards Gate (Exchange & Peoria Streets)

Designed by architect Burnham & Root and built in 1875, this limestone gate is one of the few surviving remnants of the once-sprawling stockyards.

Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (est. 1939)

One of the nation’s oldest community organizations, it became a national model for grassroots activism, focusing on housing, education, and social services.

Canaryville’s St. Gabriel Catholic Church

Founded in 1880, St. Gabriel’s has long served as the spiritual and cultural anchor of the Irish-American community.

Historical Figures from New City

Upton Sinclair

Though not a resident, his 1906 novel The Jungle immortalized the neighborhood’s stockyards and exposed their harsh realities to the world.

Joseph Meegan

A longtime alderman from Canaryville, Meegan represented the political clout and ward loyalty that defined Irish-American influence in the area.

Saul Alinsky

The famed community organizer began much of his grassroots work in Back of the Yards, pioneering tactics that would shape activism across the U.S.

Little-Known Historical Fact

During World War II, the stockyards ran at full tilt, processing up to 82% of the meat consumed in the U.S.. At its peak, the Union Stock Yards employed more than 40,000 workers, making New City one of the most important industrial hubs in the nation.

Historical Events

Opening of the Union Stock Yards (1865)

A defining moment that turned Chicago into the nation’s meatpacking capital and cemented New City’s role in the city’s industrial economy.

Closure of the Union Stock Yards (1971)

After more than a century of operation, the stockyards shut down, devastating the local economy but sparking new community-led redevelopment efforts.

Current Trends and Redevelopment

Today, New City reflects Chicago’s layered immigrant story. Back of the Yards is now a majority Latino neighborhood, home to Mexican restaurants, murals, and cultural centers, while Canaryville retains its Irish-American heritage.

Community organizations remain the backbone of New City, addressing issues from education to housing to economic development. Industrial corridors are being repurposed, and younger families and artists are finding opportunities in the neighborhood’s affordable housing stock. Despite challenges, the spirit of resilience that defined New City for more than a century still thrives.

Conclusion

New City may be best known as the home of the Union Stock Yards, but its story is far richer—a tale of immigrants, labor struggles, and community organizing that shaped not just Chicago, but the nation. From The Jungle to grassroots activism, New City has been a proving ground for resilience and reinvention.

Trivia Answer:

Upton Sinclair’s 1906 novel The Jungle exposed the harsh conditions of New City’s Union Stock Yards and directly led to the creation of the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.